James Jarché — a now largely forgotten former London Fleet Street press photographer — came to fame in 1936 as the first photographer to capture the future Edward VIII and Mrs. Simpson in public. He also broke the Fleet Street norm by not using a large and cumbersome camera such as the Graflex Speed Graphic, but preferring instead to use a much smaller, more discreet Leica rangefinder.

It was during the nationwide restrictions of Covid-19 Lockdown, in the early 2020s, that I first discovered the value of dedicated photographic webinars and YouTube videos. Since normality resumed, the YouTube algorithm continues to suggest relevant material of potential interest. While a few are hilarious or inappropriate, mostly I get apt and welcome suggestions which are refined over time.

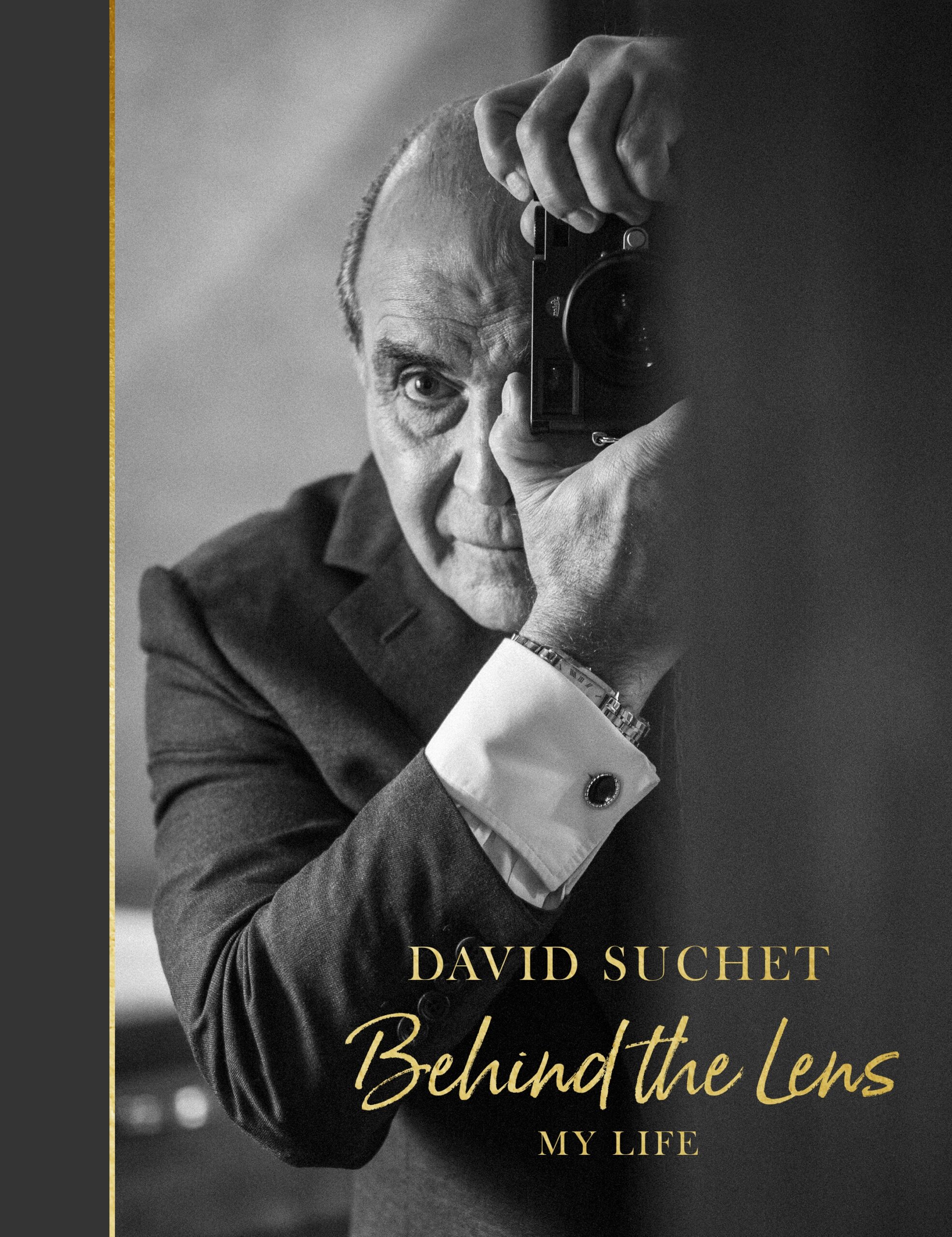

That is how Sir David Suchet’s ITV documentary, first shown in 2012, came to my notice. I was so enthralled and touched by its content, sincerity, and engagement with the people featured, that I simply had to share it with other photographers who, like me, missed it when it was first shown.

Simulated real-world assignment

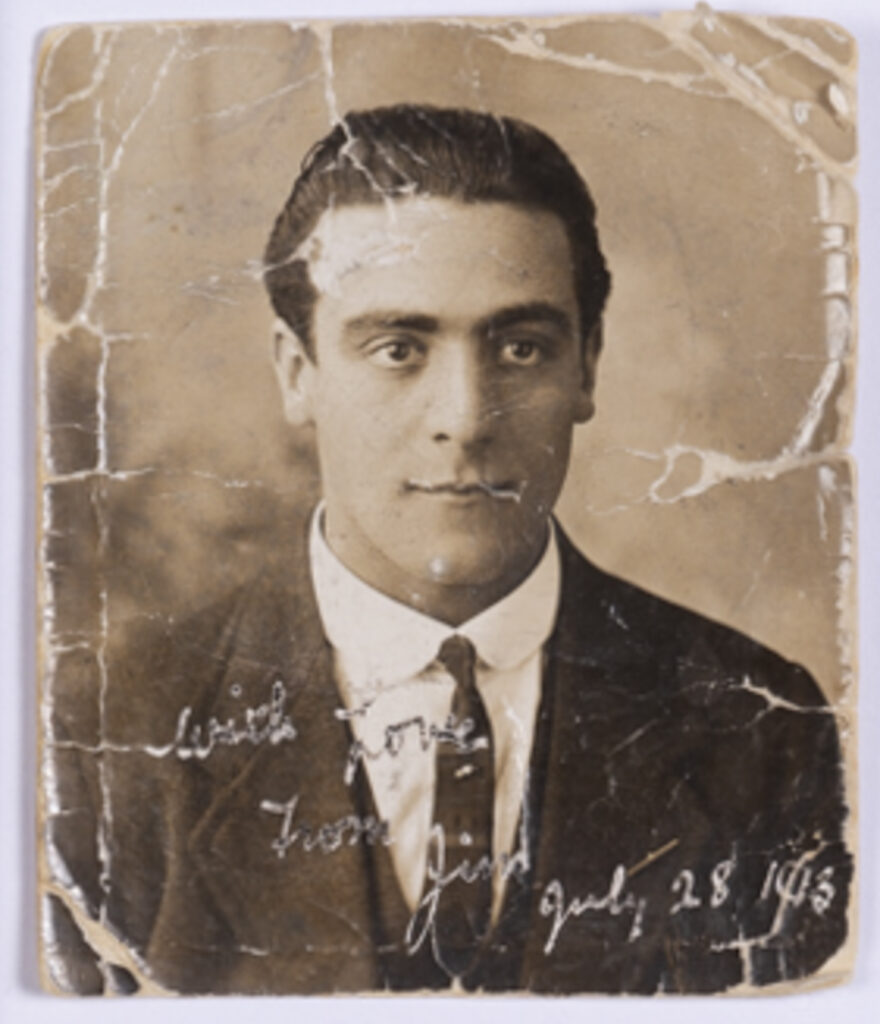

The film, narrated by and featuring David Suchet, quickly focuses on James Jarché, his maternal grandfather who he, and his two brothers, absolutely adored.

James (Jimmy) Jarché was a noted professional press photographer who was employed by London Fleet Street publishers of newspapers and leading periodicals before, during and after, World War II.

Jimmy was a lead photographer for the periodical Illustrated London News. Many of the front page photos were captured by James Jarché, especially in the mid to late 1930s. It was in this weekly journal that his unique scoop of the photograph of Edward and Mrs Simpson was published. He worked on assignments for the Daily Mirror, the Daily Sketch, Weekly Illustrated, the Daily Herald and Life magazine, among others.

James Jarché and Leica

James Jarché was one of the first such professionals to adopt the now well-established and famous Leica camera, which was the first miniature camera to use 35mm film stock. It was significantly smaller than the cameras used by other press and portrait photographers at that time.

Still, it compared very favourably with the burden of other cameramen, carrying twelve or more large format glass slides or cut-film sheets to an assignment.

With a suitcase packed and ready for a no-notice off-duty call, he was ready to travel anywhere, at short notice, to shoot a story for his editor.

James Jarché particularly liked human stories. He got on well with people from all levels of society, as does his grandson, David Suchet. This was the background which provided a feast of stories to tell his family and grandsons in his leisure time. He often regaled them with tales of his worldwide adventures.

His grandson David certainly inherited his passion for photography from Jimmy Jarché. Indeed, his grandfather taught him photography starting at the age of eight. Yet despite that earlier tutelage, David chose a very different career path in dramatic arts.

Rhondda Valley coal-mining

In 2012, David Suchet agreed to make a film for the British broadcaster ITV in which he would discover what it must have been like to be sent on assignment, work under pressure, and meet a deadline with superlative quality results.

He would learn how to overcome obstacles, meet challenging situations and still deliver a picture story worth publishing.

His first assignment was to revisit a Welsh coal-mining community in the Rhondda Valley, South Wales, photographed by his grandfather many years earlier.

He resolved to replicate the actual locations which Jimmy Jarché featured, wherever possible. But it was not long before his celebrity status was uncovered. “Don’t I know you”, asks the first local he met, “on TV maybe?”

Close encounters

Word of David Suchet’s presence in the community spread swiftly. In one touching moment, a retired veteran miner appeared clutching a much-loved old photograph, featuring his father, taken by Jimmy Jarché, many years before. David was amazed. Much to his surprise, the mine was still working, and he captured some shots of miners as shifts changed, including a father and son who were both employed at the local coal mine.

If I go back very far… the first thing I remember is his smell, a comforting, warming smell. And his smell was that of a particular pipe tobacco, Balkan Sobranie — David Suchet

In another scene, he met a lady of 87,who gave him graphic insight into life in those miners’ terraced cottages, with outside ‘loos’ in the yard, often shared by several families. She was born in the street and had lived there all her life.

These encounters with local people in the Rhondda Valley were very informative. Finally, David featured a Welsh male-voice choir, with those wonderful melodic voices drifting through the valleys, as David departed from the community. That emotional scene brought a lump to my throat.

Re-enacting the war photographer

In contrast, and tackling a different age group, David took his grandfather’s Leica M3 to a ballet school and the circus. There is a choice moment when he awaits indoors for a performer on high stilts, with enviable agility, to enter a room so that David could take a promotional portrait of the performer.

Remembering the advice given to him by The Sunday Times Magazine picture editor, David gets down to floor level to emphasise the performer’s exaggerated height. He aimed to get various shots and angles so that the editor had a good choice when laying out a multipage picture spread.

A visit to the Imperial War Museum produced some revelations for David and his brothers. They had no idea that their grandfather had served as a war photographer in Libya during World War II. He had even photographed Generals Eisenhower and Montgomery.

As a result, ITV suggested that David Suchet should re-enact the role of a war photographer in action. He would find out what it was like to get pictures in the heat of battle. Well, it wasn’t live warfare, but a simulated battle training in a relatively safe place.

“Oh damn!” he cried, with sweat rolling down from his brow, as he accidentally opened the back of his Leica M3 camera. He should have rewound his film into a light-secure cassette before opening the camera and risking fogging the film irreparably.

Such a mistake is easily made by a novice film photographer, more accustomed to the digital photography routines. I am certain that even a seasoned professional photographer was equally capable of making that mistake during the heat of battle.

David Suchet is clearly at ease meeting with strangers. On reflection, this is not surprising: “I love photographing people, just like my grandfather did. He was excellent with people. He was a people photographer.”

Obtaining correct photographic exposure was a skilful necessity in the days of film photography, entailing the use of elaborate exposure tables, independent light meters, or plain guesswork based on experience. Nowadays, with clever automation and built-in exposure metering, it is less of a challenge.

Even so, David Suchet expressed a massive sigh of relief when he saw his black and white negatives, all evenly exposed, at the processing laboratory.

Although it is well over a decade since the ITV film was made, there is one very moving moment when he tries to find someone, still alive, who his grandfather Jimmy had photographed. And he did. He found the late Queen Elizabeth II, going about her regal duties and very accustomed to being photographed. That was a second very poignant, if sad, moment in the film.

Portrait opportunities

Throughout his acting career, David Suchet was in a privileged position to photograph colleagues on and off set. He used his love of photography, and his ever-present camera, to record some memorable shots of fellow actors at work.

James Jarché conclusion

Are there lessons for a current day photographer to be learned from this documentary film? My conclusion is that good pictures must engage the viewer, hold the viewers’ attention, and pose questions. Better still, they should tell a story.

Such pictures are rare. Without engagement, any picture is quickly bypassed. Yet, with imagination and enlightenment, a picture series of three or more images can tell an interesting story. That is how and why Jimmy Jarché, and his competing rivals, succeeded.

It is more difficult nowadays because of the ease and popularity of smartphone cameras and video recording. Anyone with a smartphone can be a news gatherer. But while still photography remains so popular, it is worth adding real value to your pictures by ensuring that they do tell a story, or at least they should engage the viewer and hold the viewer’s attention. That seems to me to be a very worthy aim for most aspiring photographers.

David Suchet: People I have shot

Here is the original ITV documentary discussed in this article (just press the red start button).

Jimmy Jarché’s photographs, including his war pictures, the Sidney Street Siege and the Edward & Wallis scoop, are protected by copyright and not available to Macfilos. Instead, we have used family and other images by Sir David Suchet which are reproduced with his permission.

Note: This article is based on a much shorter one first published on the website of The Leica Fellowship in 2024, and includes deeper consideration of the historical content.

Read more from David Askham

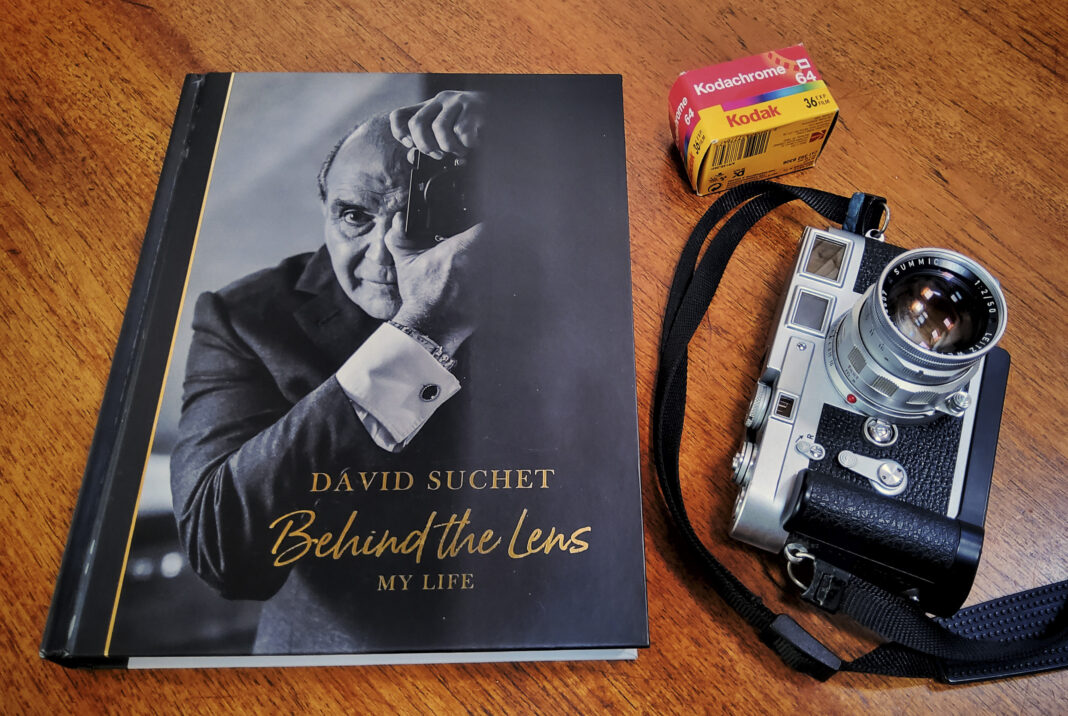

Buy Sir David Suchet’s book here

A cup of coffee works wonders in supporting Macfilos

Did you know that Macfilos is run by a dedicated team of volunteers? We rely on donations to help pay our running costs. And even the cost of a cup of coffee will do wonders for our energy levels.

Lovely article, David. I know David Suchet through The Leica Society and meeting him is always a pleasure. You can discuss anything with him; theatre, literature, religion, history and not just photography. Whatever the subject matter might be, the conversation is always stimulating. I think that on the last occasion I met him, we ended up discussing his film role as Leopold Bloom many years ago in a cinematic version of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

I love that film about David using his grandfather’s Leica. My memory was that one of the Welsh miners saw the photo of his father, taken by Jimmy Jarché, for the first time when David showed it to him. The miner then started to cry. I found that very moving, as it must have been for David, given the familial connections on both sides.

William

Thank you for this, and for the link to the Suchet video. Absolutely wonderful. Without your article, I’m quite certain I’d never have a chance to learn about this era, this photographer … and of course, Suchet. Fascinating, immediately involving stuff!

Thank you, Kathy. You are precisely the kind of photographer that I was trying to reach.

Nice article David, And one bringing back many happy days for myself as I likewise used to be a Fleet St Photographer and both knew and still have very fond memories of ‘Jimmy Jarch’ (As he was known to us all on THE Street then). What I did not know however until years later was just how good a photographer Jimmy actually was, and that was mostly because so few of we Snappers ever got by-lines in those days and so although we all had great respect for our rivals, it was only after seeing so many of Jimmy’s attributed pictures via Sir David Suchet’s TV programme that I for one thought Wow, Jimmy’s work really was truly exceptional.

Don, thank you for your kind remarks. The documentary was an eye-opener to me as well, Jimmy Jarché’s photographs reveal his virtuosity and understanding of lighting. Remember his wonderful echoing use of shadows in his shot of dancing girls on stage? And the way he captured construction workers taking a lunch break atop the Shell building in London, which would have given today’s ‘… ‘elf and Safety inspectors’ nightmares today.